This year, Subaru Canada is blowing the candles out on 40 years in business. Defined by the rugged, all-wheel-drive nature of their products, Subaru has expanded from a niche company to become an established marque. And to think it all sprang from an unusual customer request in northern Japan.

You can trace the roots of Subaru success to a handful of hastily cobbled together station wagons, with parts borrowed from Datsuns, in a rural outpost in northern Japan. For it is here that Subaru’s much-vaunted AWD system was born, the defining characteristic that would make Canadians fall for the brand head-over-snowboots.

Prior to, and during the Second World War, Subaru existed as the Nakajima Aircraft Co. Along with Mitsubishi, Nakajima produced fighters and bombers, and was broken into smaller companies after the war. One, Fuji Kogyo, began building the Fuji Rabbit scooter in 1946, essentially out of leftover aircraft parts. The Rabbit predates the iconic Vespa by a few months, and was Japan’s first scooter, a first step in the country getting back on its feet.

The Rabbit was first brought to Canada in the late 1950s by Malcolm Bricklin, a name some Canadian car fans will no doubt recognize. Bricklin, who would later found his own company and start building the gull-winged SV-1 in New Brunswick, obviously saw a coming potential.

By the time Rabbits started popping up in San Francisco and elsewhere, Fuji Kogyo had been allowed to merge with five other companies to form Fuji Heavy Industries. Its chief executive, Kenji Kita, saw car manufacturing as the next logical step in Japan’s motorization revolution and pushed through the building of a prototype called the P-1. Kita also gave his fledgling car company a name, picking out the Japanese word for the six-star Pleiades constellation, and ensuring that Subaru badges still have six stars today.

The P-1 was plagued by issues and only 20 were eventually built. More successful in the home market was the Subaru 360, a homely little machine that looked like someone had fitted wheels and headlights to one of Mickey Mouse’s shoes. In Japan, the car was nicknamed the Ladybug; when exported to the United States, even the commercials called it “cheap and ugly.” It cost $1,297, had about half the power of a contemporary VW Beetle, and could run for miles on the proverbial thimbleful of fuel.

Canada didn’t get the 360, possibly because the 10,000 Subaru 360s didn’t sell particularly well in the United States. The Subaru 1000 that followed it did a little better, but we didn’t get that one either. However, the 1000 can be considered genesis, and the key to Subaru’s success.

Jamie Cavett, a self-declared “Subaru nut” who lives in Washington State, owns several 360s and a couple of FF-1s (what the 1000 was called in the United States export market). She’s named her red 360 van Stanley and even puts out a calendar with pictures of the characterful little machine. She’s currently restoring an FF-1 sedan, perhaps the only one running example still in existence in North America.

“The difficulty is the parts,” she says, “which are impossible to find. We’ve bought up a few FF-1s over the last five years, and as many original parts as we could. We’re just about to put the carpets in the sedan, and after it’s done, we’ll be working on a wagon.”

The Cavett fleet includes a couple of modern Subarus, including a pristine 2.5RS sedan, a rally-prepped racer and a rare manual-transmission Forester XT. “When I park the FF-1 wagon next to my Forester,” she says, “you can really see the history there.”

Where the 360 was a kei-class car, and thus restricted in displacement and power to fit through certain Japanese tax loopholes, Subaru wanted the FF-1 to be a proper family car. From their aircraft-building history, they adopted the idea of an engine with horizontally opposed pistons, and the Subaru boxer engine was born. In an effort to improve cabin space and traction, a front-wheel-drive layout was chosen, a first for the Japanese market.

You can trace the roots of Subaru success to a handful of hastily cobbled together station wagons, with parts borrowed from Datsuns, in a rural outpost in northern Japan. For it is here that Subaru’s much-vaunted AWD system was born, the defining characteristic that would make Canadians fall for the brand head-over-snowboots.

Prior to, and during the Second World War, Subaru existed as the Nakajima Aircraft Co. Along with Mitsubishi, Nakajima produced fighters and bombers, and was broken into smaller companies after the war. One, Fuji Kogyo, began building the Fuji Rabbit scooter in 1946, essentially out of leftover aircraft parts. The Rabbit predates the iconic Vespa by a few months, and was Japan’s first scooter, a first step in the country getting back on its feet.

The Rabbit was first brought to Canada in the late 1950s by Malcolm Bricklin, a name some Canadian car fans will no doubt recognize. Bricklin, who would later found his own company and start building the gull-winged SV-1 in New Brunswick, obviously saw a coming potential.

By the time Rabbits started popping up in San Francisco and elsewhere, Fuji Kogyo had been allowed to merge with five other companies to form Fuji Heavy Industries. Its chief executive, Kenji Kita, saw car manufacturing as the next logical step in Japan’s motorization revolution and pushed through the building of a prototype called the P-1. Kita also gave his fledgling car company a name, picking out the Japanese word for the six-star Pleiades constellation, and ensuring that Subaru badges still have six stars today.

The P-1 was plagued by issues and only 20 were eventually built. More successful in the home market was the Subaru 360, a homely little machine that looked like someone had fitted wheels and headlights to one of Mickey Mouse’s shoes. In Japan, the car was nicknamed the Ladybug; when exported to the United States, even the commercials called it “cheap and ugly.” It cost $1,297, had about half the power of a contemporary VW Beetle, and could run for miles on the proverbial thimbleful of fuel.

Canada didn’t get the 360, possibly because the 10,000 Subaru 360s didn’t sell particularly well in the United States. The Subaru 1000 that followed it did a little better, but we didn’t get that one either. However, the 1000 can be considered genesis, and the key to Subaru’s success.

Jamie Cavett, a self-declared “Subaru nut” who lives in Washington State, owns several 360s and a couple of FF-1s (what the 1000 was called in the United States export market). She’s named her red 360 van Stanley and even puts out a calendar with pictures of the characterful little machine. She’s currently restoring an FF-1 sedan, perhaps the only one running example still in existence in North America.

“The difficulty is the parts,” she says, “which are impossible to find. We’ve bought up a few FF-1s over the last five years, and as many original parts as we could. We’re just about to put the carpets in the sedan, and after it’s done, we’ll be working on a wagon.”

The Cavett fleet includes a couple of modern Subarus, including a pristine 2.5RS sedan, a rally-prepped racer and a rare manual-transmission Forester XT. “When I park the FF-1 wagon next to my Forester,” she says, “you can really see the history there.”

Where the 360 was a kei-class car, and thus restricted in displacement and power to fit through certain Japanese tax loopholes, Subaru wanted the FF-1 to be a proper family car. From their aircraft-building history, they adopted the idea of an engine with horizontally opposed pistons, and the Subaru boxer engine was born. In an effort to improve cabin space and traction, a front-wheel-drive layout was chosen, a first for the Japanese market.

FWD traction made the 1000 popular in the snowier areas of Japan. When combined with a useful wagon variant, the practical nature of the surefooted little Subaru brought it to the attention of the Tohoku power company in 1969. Ordinarily, Tohoku used Land Cruisers or other Jeep-like vehicles to dispatch linemen to work on their power lines, but these were pretty agricultural and wearying to drive on the road. Their proposal: could the local Subaru dealership figure out how to make an all-wheel-drive version of the 1000 wagon?

At the time, Nissan had acquired a 20-per-cent controlling stake in Subaru, which meant the Miyagi prefecture Subaru could order in parts. By cobbling together drivetrain bits from a rear-drive Blue Bird (badged as a Datsun 510 in North America), and slightly raising the ride height, about eight custom 1000 wagons were made. They may properly be considered the first Subaru Outbacks.

All might have ended there had not someone from Miyagi Subaru decided to drive down to Subaru’s head offices and show off their creation. Subaru executives loved the idea and even showed off one of the prototypes at the Tokyo Motor Show in 1971. Sadly, none of the eight original cars is still in existence, the last having been destroyed in Japan’s disastrous 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

When the Leone was unveiled, better known to Canadian buyers as the DL and GL, AWD was available as an option right from the factory. In 1978, Subaru Auto Canada Ltd. (SACL) was formed from seven Subaru dealerships across Canada. This first Subaru sold in Canada was a 1978 DL four-door sedan.

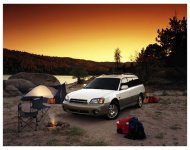

At first, Subaru AWD required pushing a button, but before long it was a full-time affair. By the late 1980s, boxy Subarus were a common sight wherever Canadians went camping, hiking or fishing. Toward the end of the decade, SACL was bought by Subaru Canada and brought under the Fuji Heavy Industry umbrella. The dealership network began to expand.

Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, Subaru would be defined by their cheery rugged nature, emphasized by rally wins on the world stage. The cars weren’t without their Achilles’ heels, ranging from minor annoyance (constant rattling) to major problem (failing head gaskets). Over all, though, the fan base grew.

Subaru appealed to the rally-racing faithful directly, starting with Tom McGeer and his Legacy GT. In 1993, McGeer managed to fend off Audi, landing Subaru their first Canadian rallying manufacturer’s title. Later, a young hotshot named Patrick Richard showed up in an Impreza with a ski rack, and began racking up unlikely wins.

Richard would go on to an enviable career, including overall wins as North American rally champion. He and his team now oversees Subaru Rally Team Canada out of Rocket Rally in Squamish, B.C., and Subaru Canada continues to support grassroots rallying, with rebates as high as $10,000 off new Subarus that will be converted to full rally spec.

Best of all, the WRX and STI might be prepped to tear up the gravel, but they’re based on practical compact cars. Your humble author recently loaded up his two kids, then one and three, and took the whole family for a 5,000-kilometre trip through the Pacific Northwest, stopping off at Dirtfish rally school so Mom and Dad could blow off steam by sliding around in the dirt. My 2012 STI hatchback hauled, in every sense of the word, the perfect choice for the enthusiast owner who still has responsibilities to think about.

You don’t have to be a gearhead to appreciate how tractable a Subaru is in poor-weather conditions. Jim Bishop, an accountant in North Vancouver, B.C., is on his fifth Outback, regularly running them into the interior for ski trips

“I put about 30,000 kilometres a year on my vehicles,” he says. “And about 20,000 of that is on snow. I’ve never been stuck in a Subaru, though I did once get stuck in my old Explorer.”

Bishop is typical of the outdoorsy pragmatism that appeals to so many about Subaru products. The Outback was perfect for hauling his family around, and now that they’re grown, it’s still a secure road warrior on the way to the cabin. Small wonder that Subaru has long proudly marketed its AWD as a safety feature.

More subtlety was required when Subaru pushed into untapped markets and began marketing to the LBGTQ community. In the United States, Subaru was cautious about the move, fearing a backlash from mainstream consumers. They were also concerned traditional Japanese corporate culture wouldn’t understand, but they also knew they needed to offer genuine advancements, such as domestic-partnership support for Subaru’s gay and lesbian employees.

Nervously, the U.S. marketing team approached a Subaru senior executive, armed with reams of presentation material to make their difficult case. The preparation proved unnecessary, as veteran ad man Tim Bennett relayed in an interview with Pricenomics, an economics and data website. “He said, ‘Yeah that’s fine. We did that in Canada years ago. Anything else?’ It was the easiest thing we did.”

Over all though, Subaru’s recent success can be credited to a focus on providing a safe choice that’s just a little outside the ordinary. Subaru continues to sponsor endurance events such as the Ironman, and generally makes the most of its outdoorsy image, but you mostly see Subies in the suburbs. A Forester or Crosstrek may be thought of as the equivalent to the puffy outdoor coat that could be used in ascent of K2, but is more often worn to the grocery store.

The $48,995 WRX STI Type RA probes the limits of what Subaru performance fans are willing to pay, while the new seven-seater Ascent takes the brand firmly into crossover country. Both, as with most Subarus, will likely sell well; the former for its rarity, the latter for its practical use.

Will Subaru be able to maintain its momentum as it moves toward more mainstream appeal? Off-road capability is still there, even if the quirks and character have been sanded away, and considerable effort has been made to position Subaru as the kind of safety-first manufacturer that Volvo is. Expect the numbers to keep growing and the sales records to keep falling. And hey, Subaru – since you’re doing so well – would a Crosstrek turbo be out of the question? Canada would love it.

Source and also further reading can be found here